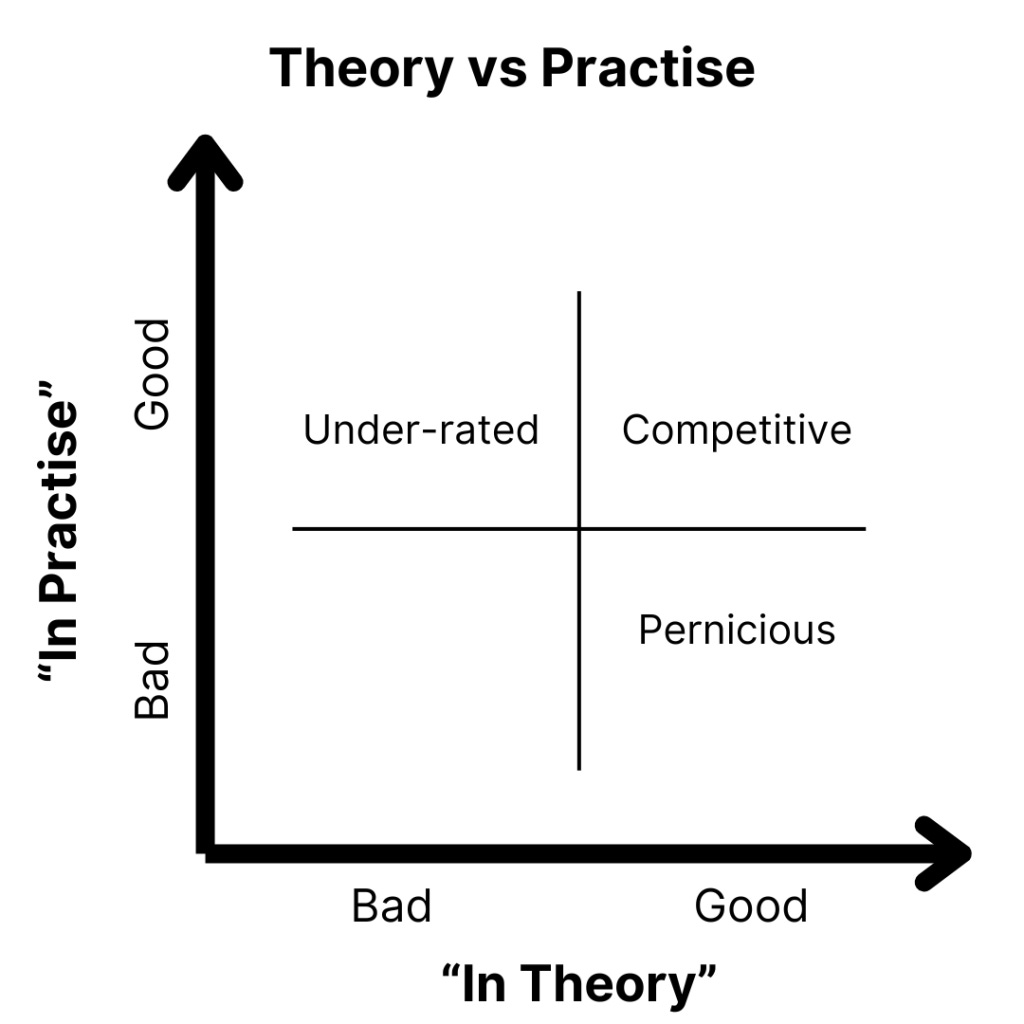

Bad in Theory but Good in Practise

I love ideas that are bad in theory, but good in practise!

Why? Well, others will try ideas that are good in theory. There will be competition.

Meanwhile, why would other entrepreneurs try out an idea that is bad in theory? They likely won’t, and, this allows for a head-start and competitive advantage.

Finding ideas that are bad in theory, but good in practise

The key to finding ideas that are “bad in theory” is to start with a good idea, and then change it – and try it – in a way that doesn’t appear to make sense. True, most of the time this won’t lead to any benefit. However, if you can cheaply try many “bad” tweaks, you stand a chance of discovering something that wasn’t useful on the surface.

I’ll give some examples…

Bad in theory but good in practise

-“Buy Now Pay Later”

Have you have been offered to “Pay in Four” when checking out online – via services like Klarna, Affirm or AfterPay? This type of offering allows customers to spread out their payments over time when making a purchase – without paying added costs or interest. Rather, it is the seller/merchant of the goods that pays Klarna the costs of “lending” the customer that money (including potential non-payment).

Now, when I first heard of this approach, I thought it was a bit of a scam. Or, “a bit of swizz” – as we would say in Ireland. To me, Pay in Four was a bad idea in theory – a credit card under a different name. Yet, in practise, it seems there is merit. Merchants would like to vary the price of their products depending on who is buying (price discrimination). Typically there is no straightforward way to do this (often because they don’t know who is buying, and sometimes for regulatory reasons). Pay in Four offers a creative way to give effectively lower pricing to certain customers. Customers that otherwise would not buy are offered what is effectively an interest free loan. Said differently, they are offered a discount. And, in practise – as (softly) evidenced by Affirm being profitable – it appears that Buy Now Pay Later does offer something better than high interest rate credit cards.

-“Selling GitHub repository access to developers”

This is how I monetize my YouTube channel. Ask a developer about this approach and they will say it makes little sense. Developers like to build things themselves, from scratch, using the abundance of free tools available online. Yet, this approach works and has been making 10kEUR+/mnth in revenue.

Good in Theory but Bad in Practise

These are particularly pernicious because entrepreneurs and academics are likely to keep pursuing them despite multiple failures. Two examples come to mind:

-“Income Sharing Agreements”

A lot of people in the US have large student loans. Uniquely, student loans cannot be discharged in bankruptcy proceedings (meaning you have them for life until re-paid). Those who take on heavy student loans and don’t get a good enough job are left in a tough position.

Enter “Income Sharing Agreements” – an alternative to loans – where students, rather than paying back the loan plus principle, pay back a percentage of their future earnings for ~10 years after graduating**. If the student doesn’t earn much, they don’t pay much. For the funding agency, those who pay back more than they received help to balance off those who pay back less. It’s great in theory!

In practise, Income Sharing Agreements are complicated for people to understand. They just want to know how much they owe. They don’t want to do spreadsheets to figure out the various outcomes. In one early startup case – that of Upstart (now a publicly traded loan provider) – clients were offered a choice of income sharing agreements and loans. Basically all customers took the loan. So, bad in practise.

I don’t rule out that income sharing agreements could succeed. But, for now, it’s a good idea in theory but challenging in practise.

**Often capped at 2x or 3x the original funding amount.

-Prediction Markets

Politicians often lack quantitative information to support their policy decisions. For example, what is the probability of China invading Taiwan? One suggestion is that there be betting markets – just like sports markets – to materialise information that supports such decisions.

In theory, this seems like a good idea. In practise, defining the specific bets in a way that is useful can be challenging. For example, it is hard to extract information on conditional bets (e.g. contingent on there being more science funding, what are the chances of electricity costs dropping below $10/kWh?). This is the kind of policy information that would be useful, but it is hard to get from a market.

Furthermore, the most useful information is often financial in nature, e.g. is defined not by a probability but by a payoff (e.g. not, “what are the chances your house is flooded?”, but, “if you pay X per year, we will insure your house up to a value of Y?”). To the extent bets are made financial, they begin to mirror financial marketsOR financial products (like insurance) that already exist. Indeed, much of the insurance market is private – i.e. there are no live public insurance prices. This indicates that achieving the liquidity needed to materialise public prices and probabilities is often difficult.

Prediction markets are good in theory, but not so straightforward in practise.

In conclusion

As Rory Sutherland says in his book on marketing called “Alchemy” – “When other people are being logical, it sometimes pays to be illogical”.

Tinker around to find ideas that are bad in theory but good in practise. You’ll find yourself alone with the keys to the kingdom. At least for a little longer than otherwise.